evEn IF yOU cAN UNdersTanD eVEry OnE oF tHese WORdS, HOW thiS SEntENce lOOks, MaTTeRs.

Beyond being an affront to CBC News style, a sentence like the one above also makes the reader work a little harder, affecting a concept called fluency.

“Fluency is just the ease with which we process information,” says Brian Scholl, a professor of psychology and cognitive science at Yale University.

Scholl’s latest research adds to the knowledge that fluency also affects how we judge what we hear, and was inspired by the way many of us communicate these days: video calls.

Hire, desire, liar

In a series of experiments, thousands of people across ages and demographics listened to short audio recordings, and were asked to make judgments afterward.

“Critically, half of the subjects heard a very rich, resonant recording,” Scholl explained, while the other group heard the same recording, “but filtered so that it sounded like it was coming through a sort of tinny microphone.”

In other words, half heard the kind of audio quality we’ve all been hearing since the pandemic thrust Zoom, WhatsApp and FaceTime calls into ubiquity.

In one example, where a male voice was applying for a job, half the participants heard the nicer sounding audio, while the other half heard the poorer quality one. Here’s a sample of those recordings, combined:

In a recent psychology experiment out of Yale University, participants heard one of these two recordings and were asked: How likely would you be to hire this person? Despite saying the same things, people were more likely to hire the fuller-sounding voice.

“What we found across many different judgments is that people were less likely to hire someone when they were speaking that familiar tinny quality,” Scholl said. Participants rated voices on a sliding scale of whether they were hireable, from “very unlikely” to “very likely.”

That hollow-sounding audio also made participants rate the speaker as less credible and less intelligent. This was even the case when the speaker was a computerized voice — meaning even the cadence of a robot was deemed more trustworthy, as long as the audio sounded richer.

One of the experiments even led participants to rate the higher quality human recording as someone they would more likely go on a date with.

Scholl says this “superficial” aspect of our communication can influence our impressions of people without us knowing it.

First impressions matter

Sonia Kang, a professor of organizational behaviour and human resource management at the University of Toronto, says that fluency and disfluency play a big role in the impressions we make on other people.

And in first-time scenarios like job interviews, the impact is greater.

“Because then you don’t have your background beliefs and historical context of this person being competent,” said Kang, who was not involved in the research. “You’re just making these quick judgments based on whatever information is coming at you.”

Scholl points out another disadvantage in virtual calls. Beyond asking “can you hear me?” (and hearing “you’re muted” far more than you’d like to admit), we don’t get much feedback on how we sound.

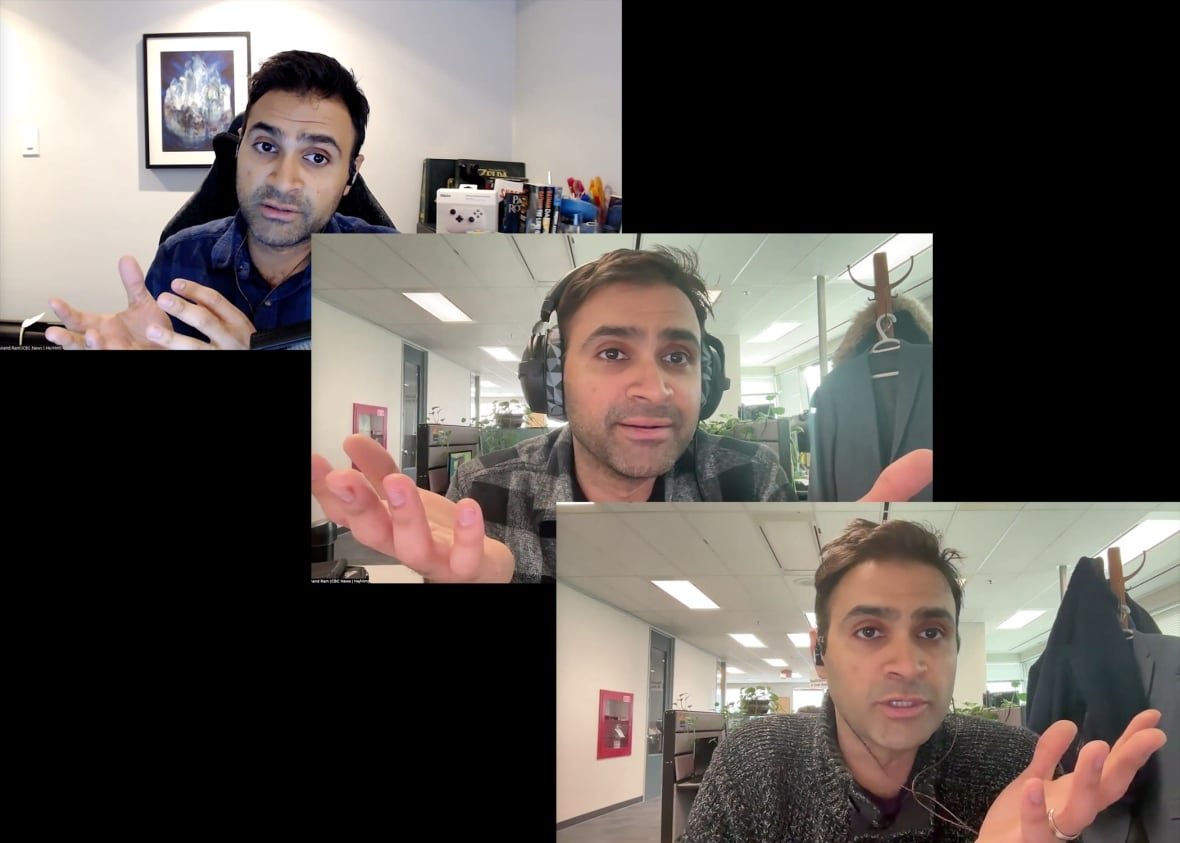

“I can see how I look, right? People do this all the time. They fix their hair, they play with their background,” Scholl said, speaking to CBC News on Zoom from New Haven, Conn., where he sometimes teaches hundreds of students via virtual calls.

“Every one of those 400 people knows exactly how I sound, but I don’t, right? What I hear is what’s coming out of my mouth. That’s very different than what you hear filtered through all these layers of technology.”

Bias upon bias

Jessica Grahn, a professor of neuroscience at Western University in London, Ont., says the study checks a number of its own biases, including pre-registering its predictions (she likens that to calling your pocket in pool) and seeing if participants were affected by their mood or whether they understood the content of the audio recording.

However, Grahn says there was a “missed opportunity to look at the demographics of the people who are answering the questions,” suggesting a test for whether genders were “equally subject to these biases or are they stronger or weaker when you’re judging across [your] gender?”

A Canadian startup is using artificial intelligence to try to reduce bias in the hiring process. CBC News visited Knockri’s headquarters to find out more about the promises its technology makes and the challenges it faces.

Grahn also commented on the experiments having been rooted in some underlying stereotypes, where male voices are more often judged on hireability and intelligence while female voices are often judged on desirability and credibility.

Check yourself

Scholl says, since COVID, a great deal of hiring is done virtually, at least at a first pass. And he says his research can inform hidden biases in hiring.

However, Grahn says there are plenty of other biases in a job interview — and in general — from attractiveness to being positively disposed to people who look and sound like us.

“Keep in mind we are all very biased people and we are influenced by things that are completely illogical and irrational,” Grahn said.

Kang suggests another pretty simple and powerful weapon: pointing out the bias to hiring managers before they start the interview.

“Something like, ‘Hey, if someone sounds tinny or distant, remember that it’s just their equipment, not a reflection of their competence,'” Kang told CBC News from Vancouver.

“This shifts their attention from the medium back to the message, so to speak.”