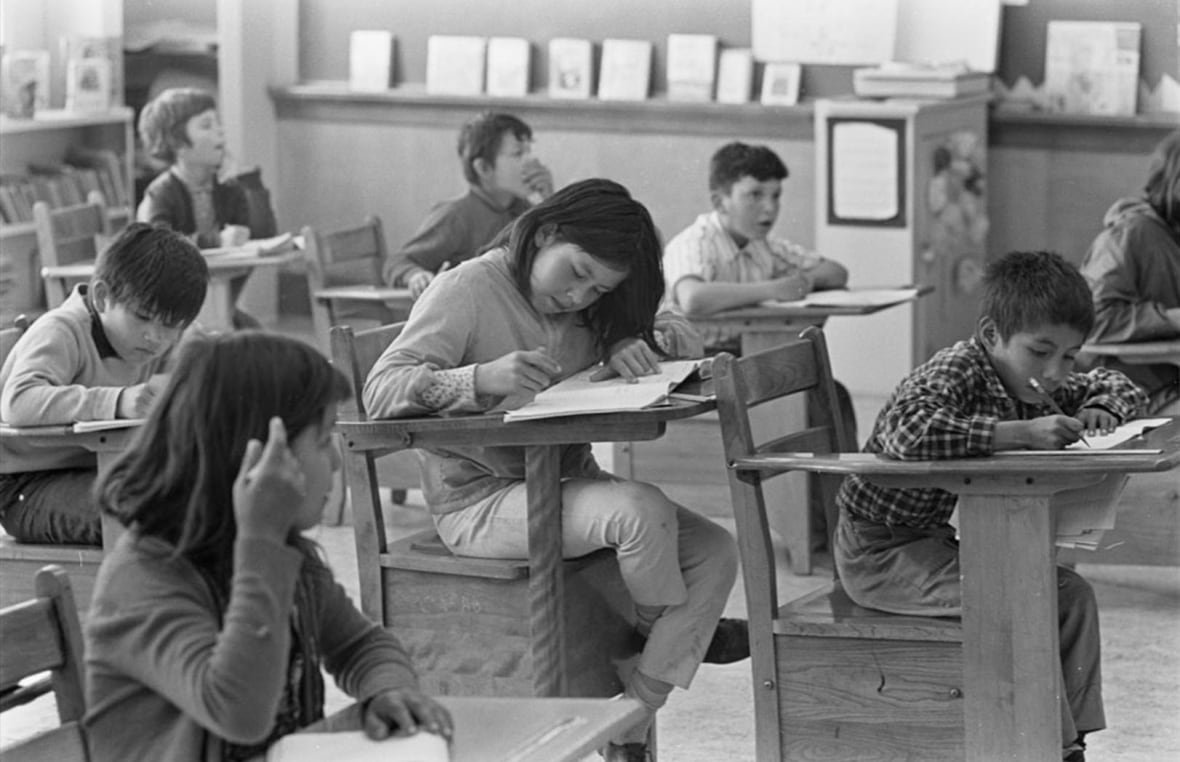

When Bryan (Fish) Googoo saw a photo of himself as a young boy posted on Facebook back in November, he was surprised.

He had never seen the black-and-white photo of himself as a five or six-year-old, sitting at a school desk, pencil in hand.

He doesn’t recall the photo being taken, whether his parents were informed or permission was given.

He does know, however, that his name wasn’t attached to the photo — until recently.

“It was being ignored through the years, those photos and what happened,” said Googoo, who is a member of We’koqma’q First Nation in Cape Breton.

“And it being brought out now, it’s a good feeling, I guess. Good to see before I pass, anyway.”

A Canada-wide project that aims to identify Indigenous people in archival images is making headway in Nova Scotia. Members of the We’koqma’q First Nation have been working to name the people who appear in photos, and as Cassidy Chisholm reports, they’ve spotted some familiar faces.

The image of Googoo is one of thousands taken of Indigenous people that are housed within the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and are now part of what’s called Project Naming.

It’s an LAC initiative that started in 2002 to add names to the photos of First Nation, Inuit and Métis people that have never been identified, decades after they were taken.

The photos are shared on the Project Naming social media pages, in hopes the people will recognize their faces and share their names to be added to the record.

Ellen Bond, the project manager, said it’s about righting a wrong.

“If there was a white person in the picture, then that person’s name was in the photo, but never the Indigenous person, and we have millions of photos at LAC,” said Bond.

“Not all of them are digitized, but it really helps to bring dignity and honour back to the photos.”

It also makes the photo searchable by name forever, she said.

In November, Project Naming posted several images from Nova Scotia, including the one of Googoo, which was taken inside the federal Indian day school in We’koqma’q, circa 1969.

Bond said the photos from the school came from another LAC initiative called We Are Here: Sharing Stories.

She said according to that initiative, the photos originally came from the information division of the federal department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

They were taken by government employees, photographers or studios employed by the department that would take on promotional projects, she said.

It’s an answer to a question that Rosie Sylliboy has had since she first started seeing the photos on Facebook: who was taking these photos and why?

Sylliboy grew up in We’koqma’q and attended the same school in the photos. She recognized a lot of the people in them and has been working to share their names with the project.

“I think to me, identity is very important … I always say it’s almost like Canada tried to erase us. So anything like this, it’s important to me,” she said.

As a lover of history, especially when it involves her community, she wanted to help connect people to these photos and pass on their stories to future generations.

In one of the classroom images, Sylliboy helped identify Bernadette Michael, who died in 2019. Her sister, Janey Michael, still lives in the area.

Michael said seeing the photo of her sister in class at the day school brings up a lot of memories.

Like residential schools, day schools aimed to assimilate Indigenous children while eradicating Indigenous languages and cultures, and often had religious affiliations. There was also widespread abuse.

Both Googoo and Michael have memories of abuse at the school.

Still, it’s important for names to be added to the photos, Michael said, including her sister’s.

“This part is like healing for me, just to be able to talk about it,” she said.

Sylliboy holds a similar sentiment.

“With our history, I think to me, it’s a form of healing because putting a name to a face, even when maybe a sibling or somebody is gone now, but just to see that face and know that we’re still thinking about them … it’s the story. It’s the story that goes with the picture.”

More photos, more connections

Googoo and Sylliboy said since learning about this project, they want to see more photos from their community, help add more names and make more connections.

Sylliboy is hopeful she can share the photos with elders in the community. She’d also like to keep copies of the photos in community for all to see.

“I’d love for us to be able to go through all those pictures and name them, because we have people in our communities that still remember these people,” she said.

“And you know, we’re losing our family members, so I think it’s critical and it’s time that we house them somewhere because we can continue sharing these stories.”